Spread Sheet

View Only

It begins with a spreadsheet, a stand-in for the Library. Paul sends me the link along with an invitation: “I'm trying to deliver the whole collection to MoMA by mid-next week (starting to photograph it now) so coming over soon, like on the weekend, would be best. Possible? (meanwhile, you can glance at the cataloguing that I'm doing here)."

I open the sheet with excited eyes. Unconsciously, irrationally, expecting to see the library itself, my gaze meets the screen’s surface. Smooth, glowing. A grid. White space. San serif. The information, as if without guile. In the moment of startlement, in the gap between anticipation and reality, the visual form of the spreadsheet itself appears with uncanny clarity.

In the upper left a green rectangle with the grid icon of Google Sheets, the title of the sheet “Library of the Printed Web at MoMA / January 2017,” a row of menu items, several greyed out, because this sheet is marked with a blue rectangle and an icon eye, meaning: View only. Paul is permissive, but not excessively. I view.

In bold, in a repeating line down the left side of the screen:

&

(Amperamp

Press)

&

(Amperamp

Press)

&

(Amperamp

Press)

&

(Amperamp

Press)

&

(Amperamp

Press)

&

(Amperamp

Press)

&

(Amperamp

Press)

&

(Amperamp

Press)

To the right are titles, bold and italic: “eSIGS, DEFACEBOOK, American Surnames Vol 1, All Time Top 100 Best Novels Vol 1, Sorry to hear this news and understand the fault is not from me, Secret Recipes, List of recurring The Simpsons characters, No network selected.” Further right, descriptions, regular weight. “A selection of signatures from PDFs. Posts from Facebook. Found list of surnames. Found book pages. A collection of spam. Recipes with 'naughty' in the title, found on Pinterest. Printout of the Wikipedia article ‘List of recurring The Simpsons characters.’” (there are the Simpsons again) “Screenshots of lists of wifi networks.” Then object type: “zine, zine, zine, zine, zine, zine, document, zine.” And then location, all US.

This meeting between me and the Library, however partial, is a good one. To begin with, the ampersand and its html representation, the amperamp—“&”—are my favorite typographic symbols. I often choose fonts just for the beauty of their ampersands. So I feel immediately among friends. Next, I detect a wave of irony from the list of titles, and I understand we are in a landscape that includes humor and satire. By the descriptions I know we are in the fields of mundane web use: detritus from email, social media, internet pop culture, quotidian moments of interaction with our devices.

There is repetition and redundancy, inherent in both the material and the spreadsheet, forcing the hand of the of an accurate describer to be repetitious as well. So I see that I am inside a system, a system with rules, and these rules are what generate sensations of beauty and ugliness, rightness and wrongness both. We are in the zone of contemporary art brutalism, an aesthetic shared by post-internet art and conceptual writing where a simple premise, carried out with the terrible thoroughness of a natural disaster, generates a novel aesthetic result. The premise of the work acts like a machine, a black box apparatus, processing the unrelenting flow of digital matter and bringing it intimately to hand.

I scroll down in a kind of free fall, watching names fly up the screen: names I know, names half-familiar, names unknown. Thick paragraphs of description texture the right-center column. At row 249, the text ends, but the sheet scrolls on, blank white rectangles until it terminates at row 1003. I especially enjoy these empty fields, where virtually nothing happens. Then I glide right across the column headings from A to AA : First, Last, Artist 2, Artist 3, Description, Object type, Location, Publisher, Year, Printing Method, Printer, Binding, Cover, Packaging, Size, Pages, Edition, Series, Platform, Key Concept, Artist URL, Work URL, PDF URL, Copies, Photography, Notes.

Like other web entities, the sheet has no fixed form. In the days that follow, I open it on various devices: phone, pad, laptop, sometimes in Google Drive, sometimes in Sheets, sometimes in a browser. The sheet is data-plus-screen, data-plus-device. On my phone, opened in Sheets, it's comically fragmentary: even the word library is cut off mid-a, but diagonal scrolling with my finger gives a strange fluid game-like feeling. At maximum zoom the text is unreadably tiny, but I get a sense of power over the whole, as if flying across a landscape. As my finger hits different cells, words and fragments appear in the function box: "laserjet," "saddle stitch," "My Google search history," "Mood Disorder documents the propagation of a photograph of David Horvitz across th," “soft."

All of this is very literal, excessively literal, but the spreadsheet itself is excessively literal. It is literal and yet strange; the literal is its form of estrangement. It echoes the works it describes. Digital content, seen straight on through the window of its context in a social media feed or a video chat is the stuff of ordinary life. Seen slant, in its full excess, it approaches the sublime. This sheet, defamiliarized by just looking, claims status as an aesthetic object.

The Body of Books

“Come over for soup,” said Paul, “and you can look at the library while it’s still here,” but by mid-afternoon we were both on Twitter seeing pictures of the crowds forming at JFK where immigrants and refugees were being detained. It was impossible to think of anything else. Paul texted: “The soup’s looking good but I’m wondering—should we head to JFK?” I put on my long underwear, packed protein bars, a bottle of water, took the subway to the air train and found Paul waiting at Terminal 4. He was carrying the baguette he had gotten for our soup and a bag of big green grapes. Neither of us had paused long enough to make a sign.

We shouted together, standing against the railing of the parking garage overlooking the crowd. "Fuck the wall!" we yelled with everyone around us. Over the people's mic we heard that a judge in Brooklyn would be ruling that evening on an emergency stay of the order. On the long ride back Paul said, "I never finished the soup, but we could have the broth at my place." So we found ourselves in Paul's apartment after all, with the volumes of the Library.

He had them stacked tightly on a low round table. They were simultaneously many and few: 244 published objects. Some were slim, zines, some were fat and glossy print-on-demand volumes, some were pro, some were spiral bound, some were wrapped in plastic, some in folders or held by clips. I opened books at random, flipping through the pages, letting the images flash in front of my eyes: screenshots, lists, grids of images, landscapes, porn, pages of mangled text, beautiful layouts, blocks of color. Impossible, really to see in such a short time. Several I knew well, many I didn't, a few I had copies of. I wanted to keep all of them.

Paul told me the story of the Library, beginning first as a following of his curiosity, then becoming a body of objects that he wanted to show people. He built a box, a cabinet on wheels, and took the Library to “Theorizing the Web”. No one had seen anything like it, and everyone wanted to know if the books were for sale. The library itself had a voice.

Many or most of the objects in the Library would be impossible to replace already, just a few years after they were made. Some were singular, or in editions of two or ten copies, others were print on demand but from sites and situations that have already disappeared. The Library is a document of a moment and a sensibility that seems simultaneously contemporary and historical—just by being gathered in this way, the manifold and subtle affects and design choices gather force and become expressive of a period. As I held the books I felt them slipping out of my grasp. The Library was about to be boxed and carried. What was left to me was the sheet.

Spread Sheet

If the sheet is an aesthetic object, a net object, then the obvious move is to capture and render it in print. Given the huge imaginary expanse of paper which is the underlying metaphor, a poster would seem obvious but, the spreadsheet is perhaps most importantly a reference, an index, a handy condensation. A pocket sized book comes to mind. The most useful form of a such reference might have 244 pages—one for each item in the library—gathering the information as neatly as possible, but this would betray the nature of the sheet. The primary characteristic of the spreadsheet is not the way it gives information, but how it withholds: it simultaneously offers and frustrates, displays and hides. What you want to see can never be seen in one glance, much is invisible or cut off at the edge of the screen, even as the ‘sticky’ cells persist in every view, taking up a good portion of what is seen and seeable. Let us choose fidelity to this fragmentary, halting, repetitive, irritatingly real view.

I begin with screenshots, capturing rectangles of the sheet in dimensions that correspond to my view, dragging the cursor in diagonals across the screen, positioning the rows and columns, from 0,345 to 703,518, then 345,697 to 703,518, repositioning columns and repeating. I copy and place each layout in inDesign: a screenshot per page, five pages for each set of visible rows. I love this kind of digital artisanal labor, where the human worker sits in front of a keyboard and screen, handcrafting what becomes the seamless looking surfaces of web and print publications. Whenever I take up one of these tasks I feel the pleasurable weight of countless hours of repetition lying before me. Of course, there are boredoms, but there are corresponding satisfactions, as if the interfaces of TextMate, MYSQL, Preview, Photoshop, InDesign, web browsers, and the rest are very bland video games.

Like many such tasks, there is something inherently absurd about this one. What seemed to be a unitary object (the spreadsheet) has become 260 pages of screenshots. Scrolling the spreadsheet in its natural habitat is fluid; transferring it into print is chunky and effortful. I feel the error-prone intimacy of my own humanness playing against the machinic precision of code and the lucid optimism of design. As I work, I listen to an audiobook of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, less dystopian than the news.

Some of the work in the Library is completely scripted from conception to printing, but much of it requires precisely this, repeated human selection, adjustment, placement. The digital does not imply the automatic—it most often requires intimate human action. Coding itself is an bodily action (just think of all those cups of coffee). Even this text happens at the human boundary of the artificial, written into a laptop, my fingers moving across the keys with little taps of beautifully calibrated audibility.

Between the Dream and the Body

I once spent a few thousand hours with Visicalc, the first commercial spreadsheet: long days and nights filling the black screen of a primitive monitor with vivid phosphor-green numbers describing imaginary business scenarios. In this way, the perceptual experience of the earliest spreadsheet technology was fused with the hedonism and hubris of being 22 and in a startup, ostensibly in charge of dreaming. I was writing the plan for our next phase, making documents to convince venture capitalists of our promise. Visicalc was like magic: if profitability looked too far off, sales projections could be increased with a few taps, expense estimate formulas reduced, and beautiful changes would ripple across the sheet. The spreadsheet, as invented, is a form of imagination. It offers itself as an index to reality, but is in fact helpless in the face of whatever information you enter. Between the user and the spreadsheet is a dream. Which is more intimate, more human: dream or body? The representation or the represented?

I want to put my hands on one of the books. Step away from the index and towards the real. I know I own, for instance, David Horvitz’ Mood Disorder, but my own library is disorderly; searching through my piles, I find instead his book Watercolors. I wonder, did I ever have Mood Disorder in the first place? The book is a thing that can be present or absent, physical or imagined. A book, like a body, can be mistaken. How many times had I come across Watercolors and thought it was Mood Disorder? Or was it Public Access that I have somewhere?

In the spreadsheet, I scroll down the alphabet to the H’s, a bit jerkily since the internet in my studio is stubborn and slow, but once I arrive I can just slide along row 83. Where the body of the book is not to hand, the description is: “Mood Disorder documents the propagation of a photograph of David Horvitz across the internet.” I can easily picture the photo, which I’ve seen countless times. “The image—a self portrait of the artist with his head in his hands, ocean waves crashing in the background—was initially uploaded to the Wikimedia Commons, and placed on various Wikipedia pages. From there, the image began to circulate, appearing on over a hundred websites as a “stock” photo to illustrate articles on a wide range of mental health and wellness issues.”

This seems like a place to land, a story. But the row goes on and tells another story: book, US, New Documents, 2015, offset, saddle-stitch, soft, 9.875 x 13.75, 72, 2,000, Wikipedia, image circulation, http://www.davidhorvitz.com/ https://new-documents.org/books/mood-disorder, 1, X, purchased at NYABF. The cataloguing entries speak of the object of the book, its making, its size, and ultimately its presence on a table at Printed Matter’s New York Art Book Fair where Paul picks it up, pages through it, takes it home.

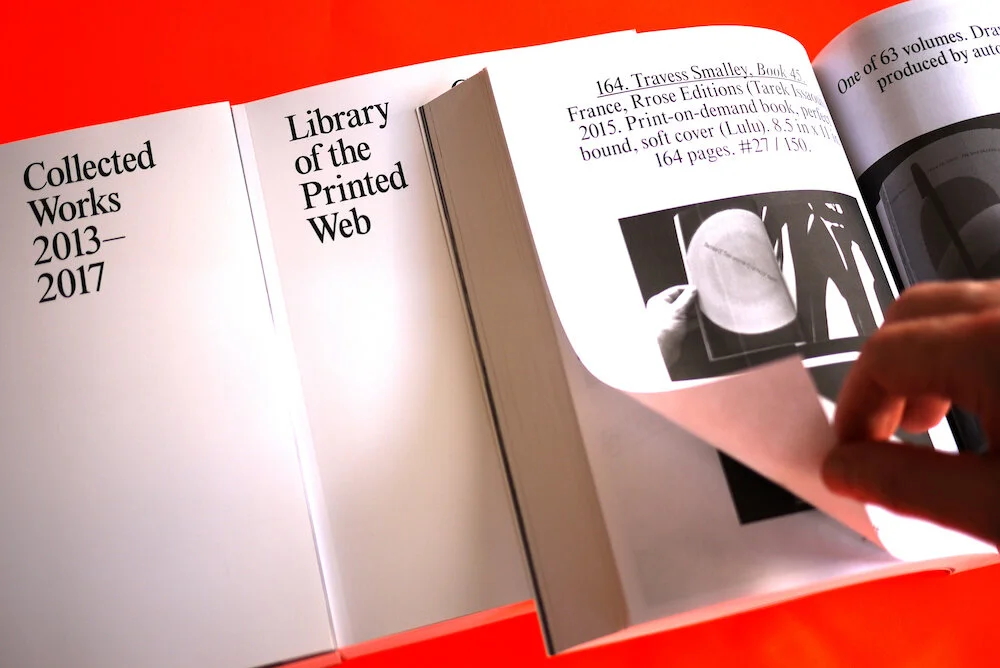

“Spread Sheet” is included in the catalog, Library of the Printed Web: Collected Works 2013–2017(2017) by Paul Soulellis, which documents the Library of the Printed Web as acquired by MoMA (photo: Paul Soulellis).